Dr. Simona Valeriani

The Royal Albert Hall, an iconic Victorian building, constitutes a perfect case study to reflect on the role played by models in the design process in the mid-nineteenth century. Models used at all stages can be read not only as design aid within the architectural culture but also as part of a broader culture of experimentation characterizing several areas of professional, industrial, and academic life in the period, and particularly in the milieu of the Royal Engineers, highly involved in the construction of the Royal Albert Hall and the South Kensington project.

The genesis of an idea

Following the Great Exhibition of 1851 and its considerable financial success, the idea took shape to transform South Kensington, the area neighboring the spot where the exhibition had been staged, into a new “cultural quarter.” Museums, exhibition spaces, educational institutions, meeting spaces for learned societies, and a music venue were some of the main buildings and functions envisaged.

While the idea of a new museum in this area could be realized relatively quickly—the South Kensington Museum (today the V&A), founded in 1852, opened in its current location in 1857—other parts of the project took much longer to materialize. In particular, the plan to build a great hall, which would serve as a meeting space for learned societies, as an exhibition space, and as a music venue, was slow to get off the ground. By the early 1860s, plans envisaging the construction of a building at the north end of the Commission’s grounds, adjacent to the Royal Horticultural Society’s conservatory and opposite Hyde Park, had settled.

When Albert died in 1861, the idea to erect a national memorial dedicated to him at South Kensington emerged, and the hall was conceived to be part of it.

The hall’s design was entrusted to the Royal Engineer Captain Francis Fowke (1823-1865) who, however, prematurely died in 1865, when the hall was still an unconfirmed project, which had only partially taken shape. Archival sources document how he had developed detailed plans for the interior but was still working on the exterior. Fowke’s preliminary ideas found their embodiment in a model presented to Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales on January 30, 1865, hoping to gain their support for the project. This was the first of a rich series of models produced in connection with the Hall.

Before diving into the specifics of the Royal Albert Hall’s many models and their functions, it is important to understand better the role programmatically attributed to models by the designers involved in the construction of the Hall.

Models and experiments

Henry Darracott Scott (1822-1883), Major-general of the Royal Engineers, who was put in charge of the construction of the Royal Albert Hall from 1865, when his predecessor died, described the process of designing buildings in this way:

- The director of New Buildings prepares experimental plans and sections […].

- Block models are then made, but without inserting architectural details. Several models are generally made and experiments tried […].

- When the block model has been settled the structural plans with sketches are finally made […].

Francis Fowke, Henry Scott, and The Royal Engineers were very involved in constructing public buildings in London and extensively in South Kensington in the mid-nineteenth century. They took an experimental approach to design, relying heavily on models of different kinds and scales, including 1:1 models. An instance of the adoption of this process is documented for the design of the Memorial of the Exhibition of 1851. A series of experiments were conducted from March 11 to May 17, 1861, at the South Kensington Museum. To oversee the process, HRH the Prince Consort visited this site upwards of eight times. One such visit is memorialized in a painting by Anthony Stannus (1830-1919) (Figure 1).

Experiments with the Model of the Memorial of the Exhibition of 1851, Erected in the Royal Horticultural Society’s Gardens before the Design was Settled by HRH the Prince Consort. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK, E929-1976.

The Prince, accompanied by General Charles Grey (1804-1870), Mr. Richard Redgrave (1804-1888), and Captain Fowke, and observed by Mr. Cole, views the Model from a pit dug so that the eye of the spectator would be at the right level, simulating the viewing conditions of the monument in its final location (Figure 1).

The many examples of experiments conducted using models to develop designs at South Kensington need to be understood in the context of an experimental culture characterizing the Royal Engineers in the period. At Chatham, the Royal Engineers’ training centre, the production and manipulation of three-dimensional models were, programmatically, an integral part of the training.

Thinking in 3D: modeling the Hall

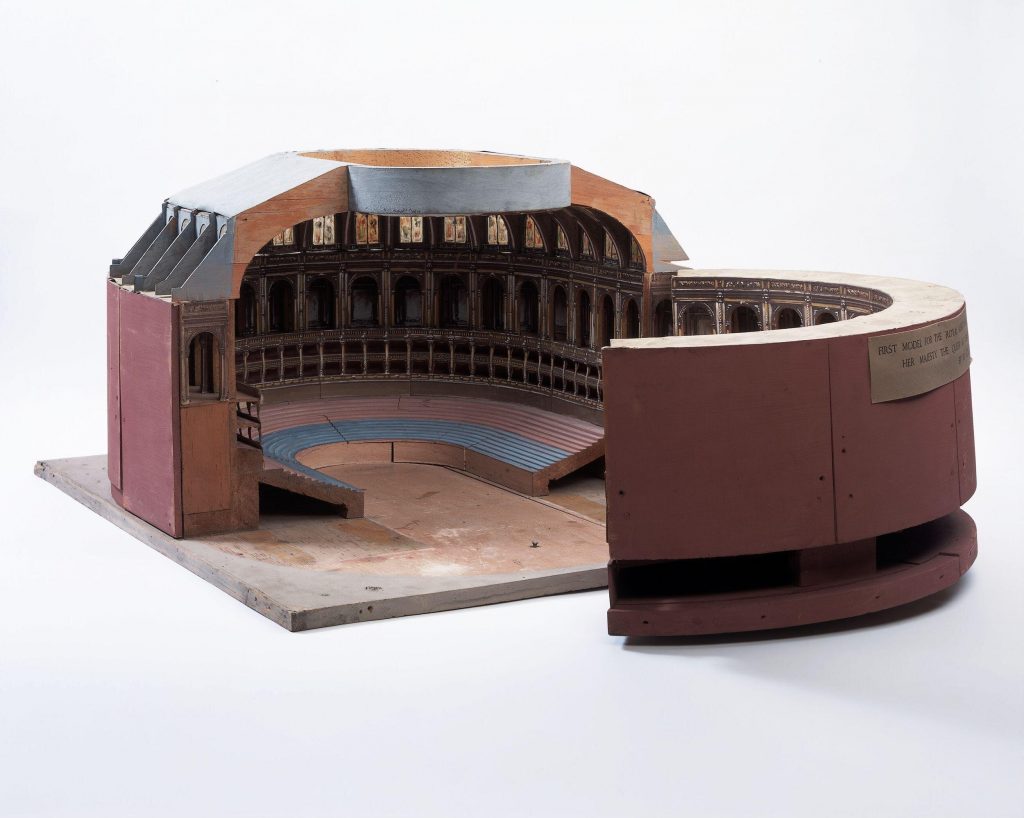

The experimental approach becomes particularly evident in the Royal Albert Hall’s construction, where numerous models were produced to fulfill different purposes. The first model of the Hall, built at the South Kensington Museum, at the time also home to the School of Design, shows Fowke’s design for the interior of the building (Figure 2). Presented to Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales in January 1865, it demonstrates how the project was developed from the inside out, starting by making tangible the interior space.

Other models were produced after Fowke’s death. This was a delicate moment in the history of the hall, when discussions took place to consider if an architect was needed to complete the project in light of the plans and memoranda already available. Given the financial limitations characterizing the venture, the movers behind the project, such as Henry Cole and General Grey, were keen to keep costs down and thought that an architect would require pricey fees and produce a more expensive project. They were inclined to believe that Fowke’s draughtsmen might be able to complete the design.

At this stage, Cole proposed to have models made from Fowke’s drawings and memoranda and use them as a basis to collate suggestions for improvements from a pool of architects. From a letter to Cole written on April 13, 1866 by the Earl of Derby (1799-1869), we learn that a plaster model was produced. The Earl of Derby suggested meeting “in the reading room of the Horticultural Society where the Plaster Model of the Hall can be put up & Fowke’s drawings and designs laid out for consideration.”

In these conversations, the need for a skilled professional to coordinate the project’s development became apparent. Eventually, the Royal Engineer Henry Young Darracott Scott (1822-883) was chosen. However, to obviate what some considered his relative inexperience in the design of architecture rather than the construction of functional military buildings, a Committee of Advice was formed, bringing together highly skilled and well-known professionals.

The committee based its discussions and assessments mainly on models. For example, in July 1866, a wooden model, itself the result of discussions within the building committee around first sketch models, was used to approve and refine the design:

[the committee] decided that its general arrangements should remain as therein shewn [sic], but the committee desired to have the opportunity of judging whether similar arches and columns throughout or lunettes of bold character might not be substituted with advantage for the arcade shown in the model.

The same model was used at subsequent meetings to visualise and discuss suggested alterations.

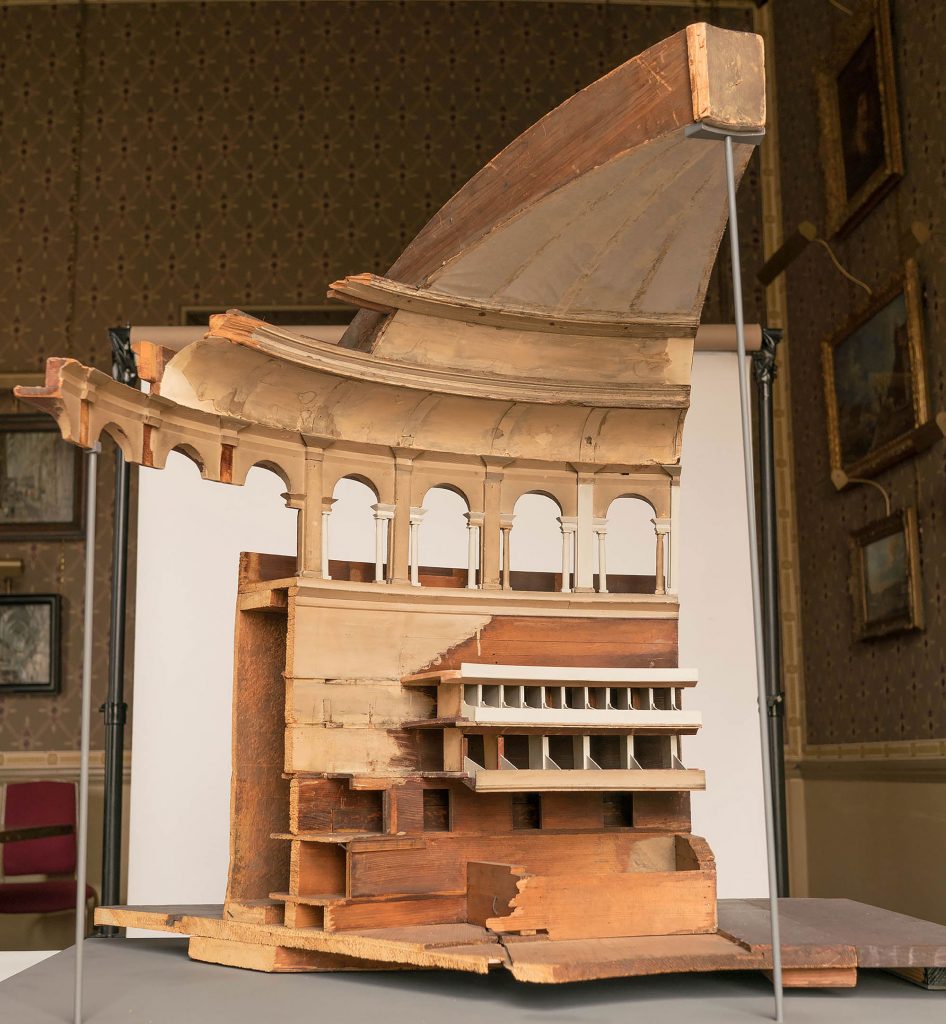

Until recently, none knew what this model looked like. However, in 2018, a portion of a model was found in a cupboard, hidden at the back of a storage room at the Royal Albert Hall (Figure 3), which can be reasonably assumed to be the one referred to in the minutes. This model testifies to a process of progressive transformation and constant reworking, following consultations and subsequent evolutions in the Hall’s interior design.

The materiality of the model confirms its role as a design and discussion aid. For instance, despite its current fragmentary state, there is evidence that it was constructed to be easily taken apart: the roof structure could be lifted, and the side opened. Moreover, it is not a highly finished object. It bears witness to different strata of paint and, possibly, changes to the solutions adopted for the Hall’s interior organization. The exterior was kept simple, with a colored drawing of the façade glued unto the wooden surface (Figure 3, right). The façade depicted is similar to the one that was eventually built, the design of which was chosen only quite late. It is possible that different façade drawings were pasted to this model as the design progressed.

More detailed models were made to work out interior details such as the stairs arrangements and the seats. Staircases are often a tricky aspect of a design, and it is not unusual that models of staircases were made.

For the definition of the Hall’s exterior, a number of models were made. Fowke had not developed this aspect and Cole and his associates were facing a significant challenge. In July 1866, Cole suggested to set up a competition to design the exterior of the Hall, which would take a model as a starting point:

[I suggest] to prepare the model as far as may be done, consistently with what we believe to be Fowke’s wishes […].

To let the architects see it and then to give a premium or premiums to those who can suggest the best practical improvements […].

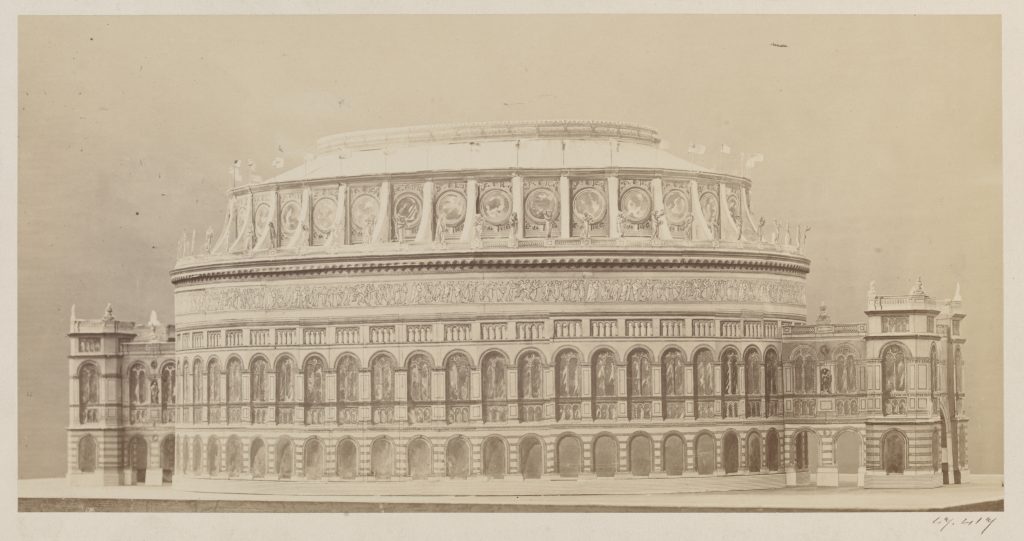

We do not know if this was ever done, but we do have evidence of a series of models made to develop the design of the façade. Some models of the overall look and façade design survive in photographs (Figure 4). Such models must have been made early, possibly in 1866, since they experimented with different entrances and staircases.

In 1866, Henry Scott worked closely with Fowke’s draughtsmen, including John Liddell. The latter produced some drawings of the Hall, including at least an elevation used in July 1866 by the Committee of Advice to discuss possible ameliorations to the design.

While modifications to the design of the interior were being worked out based on a model, modified from one meeting to the next, the exterior was mainly discussed considering drawings. The committee agreed on a solution using a combination of media.

Having examined the alterations in the drawings and model suggested at the last meeting, we approve of the central of the 3 treatments of the intended arcade, and of the central bay of the drawings of the exterior, and consider that the alterations suggested have been fully carried out.

This, however, did not mark the endpoint of the design process, and subsequent phases, again, made extensive use of models. Almost a year after the Committee of Advice’s decisions mentioned above, Mess Hunt & Stephenson presented their estimate of the cost of the building. The total sum amounted to £235.000 and was, therefore, well above budget (£175.00). Subsequently, substantial changes were made to reduce cost. For example, it was decided to leave the external staircases out and omit the mezzanine storey between the lower gallery and the picture gallery.

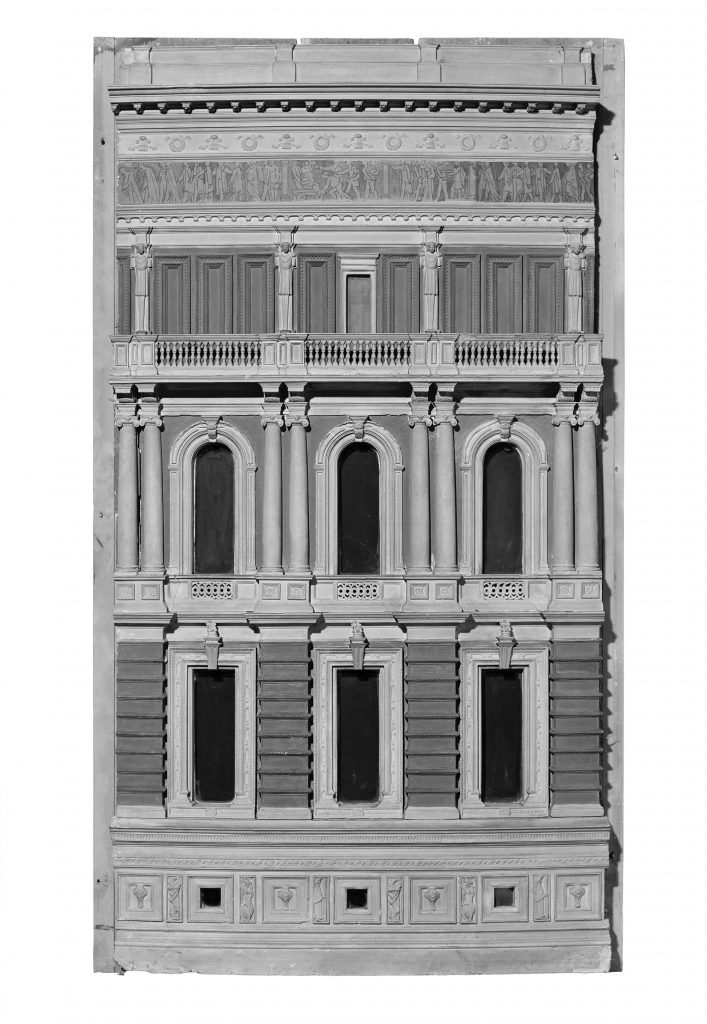

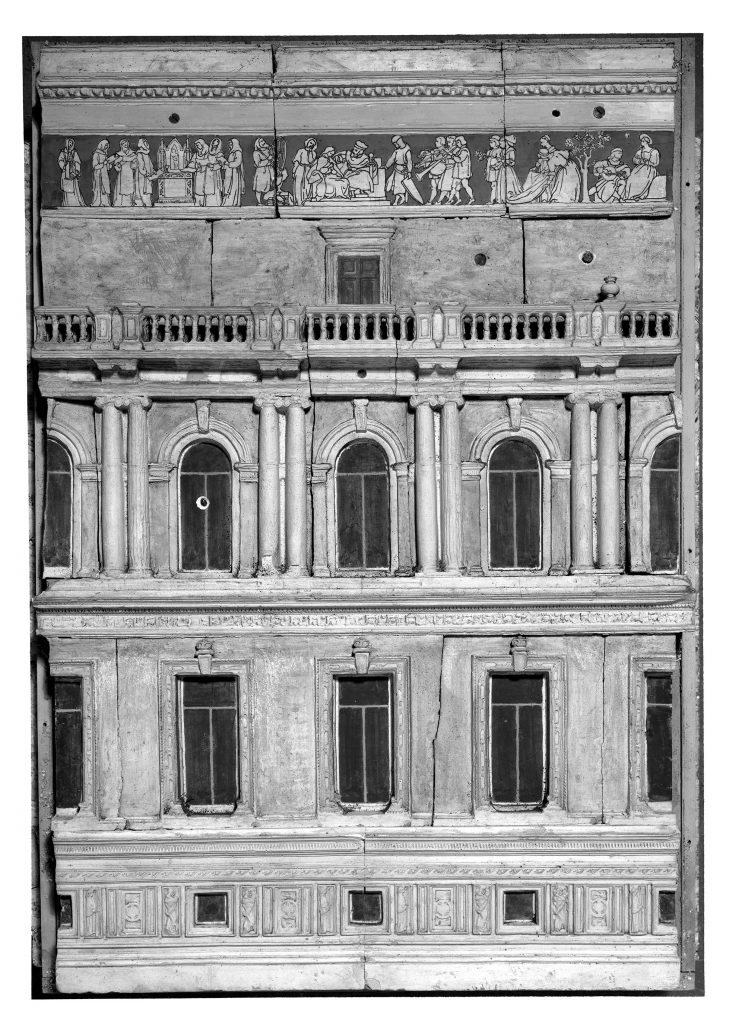

These cost-saving modifications to the design also involved simplifying the terra cotta dressing for the façade, which is documented in a series of models preserved at the V&A (Figure 5). In their features, these three miniatures of a portion of the Albert Hall’s exterior represent progressively ‘plainer’ versions of the design, starting with a façade characterized by several sculptural elements and figurative reliefs, which would have given the Albert Hall’s exterior a very different feel.

The base of the edifice, hosting the ground floor, presents in all three models a more elaborate decoration than the extant building, as the square windows are flanked by vertical rectangular panels that seem to be filled by figures. However, space in-between the vertical panels is in one case filled with a decorative element (possibly a vase), while in the others it displays a simpler treatment, not dissimilar from the one finally adopted, whereby the center of the circle now contains shields exhibiting the arms of personages and institutions connected with the Albert Hall’s construction.

Most probably, the first model (Figure 5, left) represents an earlier design that was developed in detail and constituted the likely basis for building the Albert Hall, until financial constraints forced Scott to go back to the drawing board. Evidence of this is the great care and expense in making the curved model (Figure 5, left), mimicking the shape of the Albert Hall. It could be considered a presentation model, made at an advanced stage of the design to gain approval. In comparison, the other two models (Figure 5) look like working and discussion tools. They are flat models, not taking the Albert Hall’s curvature into account. Moreover, they seem to be constructed with movable parts that allow different variations to be ‘slotted in’ and tried. The V&A also holds a couple of partial façade models that presumably were used in this way.

The final solution for the enrichment of the upper part of the façade, today characterized by a mosaic frieze, seems to have been agreed upon as late as in the summer of 1868. Cole noted in his diary that in April of the same year, the painters Daniel Maclise (1806-1870), Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), and Albert Joseph Moore (1841-1893) were being considered to execute what probably was a flat pictorial scheme.

In order to resolve design challenges at the Albert Hall, some parts were even modelled in real size. In particular, this applies to the mosaic decoration for the frieze. Cartoons were used when deciding on the most efficacious size for the figures. The design had been reproduced in different scales and the cartoons were affixed in the South Kensington museum at an appropriate distance to judge which one would be most appropriate. The use of 1:1 mock-ups was not unusual on the South Kensington building sites. A portion of the Horticultural Gardens’ arcade was built as a trial in the Museum grounds “and very much altered from time to time, till what was to be the final result was arrived at.” This extensive use of 1:1 models is to be considered in the context of the military engineering training and experience of Fowke, Scott, and many of the main actors involved in designing and building at South Kensington.

Richard Redgrave, a close collaborator of Cole’s, was asked about this method during his testimony to a parliamentary inquiry. He observed that, in Britain, he had only seen it employed at South Kensington, but it was not unusual in the international context. As a comparison, he mentioned the Barrière du Trône in Paris. This historic place had been the theatre of momentous events during the revolutionary years and, between 1845 and 1862, plans for a re-design unfolded. As part of these initiatives, in 1862, a full-scale model of a new triumphal arch was erected on the place and unveiled to the Parisians. Using this example as a starting point, Redgrave explained how, in his opinion, it is important to use models to communicate to the wider public the designers’ intentions and to gauge reactions, despite warning about the reliability of public opinion, considering that many are ill-equipped to make artistic judgments.

It seems that the Albert Hall’s building site itself, at a certain point, was being used as a sort of trial ground or full-scale model. Newspaper reports from May 1869 inform us that:

A slight notion is got of the vast size of the interior when catching a remote glimpse of a piece of wood, rudely cut to represent a human figure, and painted white. We learn that this spec is the full-size outline of a vocalist placed where she would stand in the building.

A sizable amount of money, particularly considering the limited budget available for the project, was spent on models. From an estimate dated March 1867, we learn that £324.66 had already been spent by then for models, while forthcoming expenses comprising “the remuneration to the architect, the cost of modeling & other charges” were estimated at £15.000.

It is unclear if the sums spent by March 1867 comprise the expense for producing a model for the International Paris Exhibition. This was not an experimental working model but a presentation model to showcase the project to an international audience, in an effort to publicize the new building. In this period, the project was, in fact, ready to be shared with the public on different levels, and it was also presented at the Royal Academy exhibition in London, where design drawings were on show. Alongside these high visibility public spaces, other venues served a similar purpose. As publicized in newspapers, a wooden model of the Hall, in 1869, was “to be seen in one of the private apartments of the South Kensington Museum.”

Similarly, in the early phases of the project, when consensus from the political and social elites was being sought, General Grey was inviting the Hall’s vice patrons, members of the Commons and the Lords to go and see the model in his office. He hoped that this would motivate them to become subscribers. Later, a similar ‘advert’ inserted in the prospectuses distributed to potential subscribers, directed them to the contractor’s office at the Prince Consort’s memorial on Hyde Park.

This evidence, taken together, confirms the importance of models in the Albert Hall’s history, underlining the functions these artifacts played in the second half of the nineteenth century in England, as a tool in the design process and as a communication tool between designers and patrons as well as a means to gain general public consensus.

Bibliography

Albert, Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. 1853. “Memorandum by Prince Albert regarding buildings at South Kensington.” 20 August, Commission of the 1851 Exhibition’s Archive: RC/H/1/A/3/1.

Christ, Yvan. 1977. Paris des Utopies. Paris: Éditions Balland.

Cole, Henry. 1868. Diary, 6 April 1868. National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, MSL/1934/4145.

Cole, Henry. 1866. Letter to General Grey, 1 April 1866, Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 Archive: RC/H/1/21/64.

Committee of Advice. 1866a. Minutes of the meeting held on 26 July 1866. Royal Albert Hall Archive: RAH/1/2/1/15.

Committee of Advice. 1866b. Minutes of the meeting held on 6th August 1866. Royal Albert Hall Archive: RAH/1/2/1/17, p. 61.

Executive Committee. 1867a. Minutes of the meeting held on 28 March 1867. Royal Albert Hall Archive: RAH/1/2/1/21, p. 73.

Executive Committee. 1867b. Minutes of the meeting held on 4 April 1867. Royal Albert Hall Archive: RAH/1/2/1/22, pp. 80-84.

Grey, Charles. 1865. Letter to members of the Commons and the Lords, 1 December. Royal Albert Hall Archive: RAH/1/2/1/3: 32.

Grey, Charles. 1866a. Letter to Lord Derby, 15 February. Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 Archive, XXI.181.

Grey, Charles. 1866b. Letter to Henry Cole, 13 April 1866. Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 Archive, RC/H/1/21/65.

“The Kensington Amphitheatre.” 1869. The Builder 10 April: 278-279.

Leslie, Fiona. 2004. “Inside Outside: Changing Attitudes Towards Architectural Models in the Museums at South Kensington.” Architectural History 47:159-200.

Ducuing, M. François. [1867]. L’exposition Universelle de 1867 illustrée. Paris: Impr. générale Lahure: 2.

“Our Rambler at South Kensington”. 9 January 1869. The Architect and Building News: 20-2.

Pasley, Charles William Sir. 1861. Outline of a Course of Practical Architecture. Chatham: Established for Field Instruction, Royal Engineers Department.

Redgrave, Richard. August 2, 1869. Parliamentary Papers, 1868–9, x, ‘Second Report from Select Committee on Hungerford Bridge.’ London.

Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851. 1851. Albert Hall of Arts and Sciences Prospectus. 1865. Archive of the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, RC/H/1/20/82.

Scott, Henry Y. Darracott. 1872. “On the Construction of the Royal Albert Hall.” Papers Read at the Royal Institute of British Architects. Session 1871-72: 82-100.

The architect and building news. 1866. 3 March: 145.

The architect and building news. 1867. 25 May: 366.

Valeriani, Simona. Forthcoming [2023]. The Royal Albert Hall. Building the Arts and Sciences. Turnhout: Brepols.

Wells, Matthew. 2018. “Architectural models and the professional practice of the architect, 1834–1916.” PhD thesis. London: Royal College of Arts.

[1] This text bears many similarities with a longer one published by the author in print: Valeriani, S. ‘Life and Afterlife of a Design Process: Models and Drawings of the Royal Albert Hall’, The Routledge Companion to Architectural Drawings and Models: From Translating to Archiving, Collecting and Displaying edited by Federica Goffi, 2021. For a complete history of the Royal albert Hall’s building history see Valeriani, Simona. Forthcoming [2023]. The Royal Albert Hall. Building the Arts and Sciences. Turnhout: Brepols.